You and a rock are both made of atoms. The same kinds of atoms, in fact — carbon, oxygen, hydrogen, the usual suspects. The rock has been sitting in a field for ten thousand years, undisturbed. You have been here for a few decades and have rearranged the world in countless small ways. What is the difference?

Not what you are made of. Not what you are "thinking" or "feeling" — those are famously slippery concepts that philosophers have argued about for twenty-five centuries without converging. The difference is simpler than that. It is what you are doing.

And the answer turns out to be three things.

Three things an agent does

You survive by effort. Not by accident, like a rock surviving because nothing has smashed it. By work. Your immune system fights off infections. Your cells repair their own DNA thousands of times a day. When your blood sugar drops, you feel hungry and go find food. You are not passively persisting. You are actively maintaining your own existence inside a narrow band of conditions — and the moment the maintenance stops, you begin to fall apart.

You choose. Not in some grand metaphysical sense. In a boring, measurable sense: there are multiple futures available to you, and which one happens depends on what you do. Turn left, you reach the park. Turn right, you reach the store. The world after your action is different depending on which action you take. A rock has no such leverage. After a rock does nothing, the world is the same as if the rock had done nothing — because that is all a rock can do.

You persist as you. Not as a generic entity, but as a specific, recognizable pattern. Someone who saw you yesterday and sees you today identifies the same person. Your description holds up under repeated observation. You are not flickering in and out of coherence like a candle in the wind. You are the same package, moment to moment, because something is working to keep you that way.

These three things — maintained survival, real choices, and stable identity — are what separate an agent from a thing. Not consciousness. Not intentions. Not free will. Three measurable properties that you can check without ever opening the hood and looking for a soul.

The spectrum from rock to cat

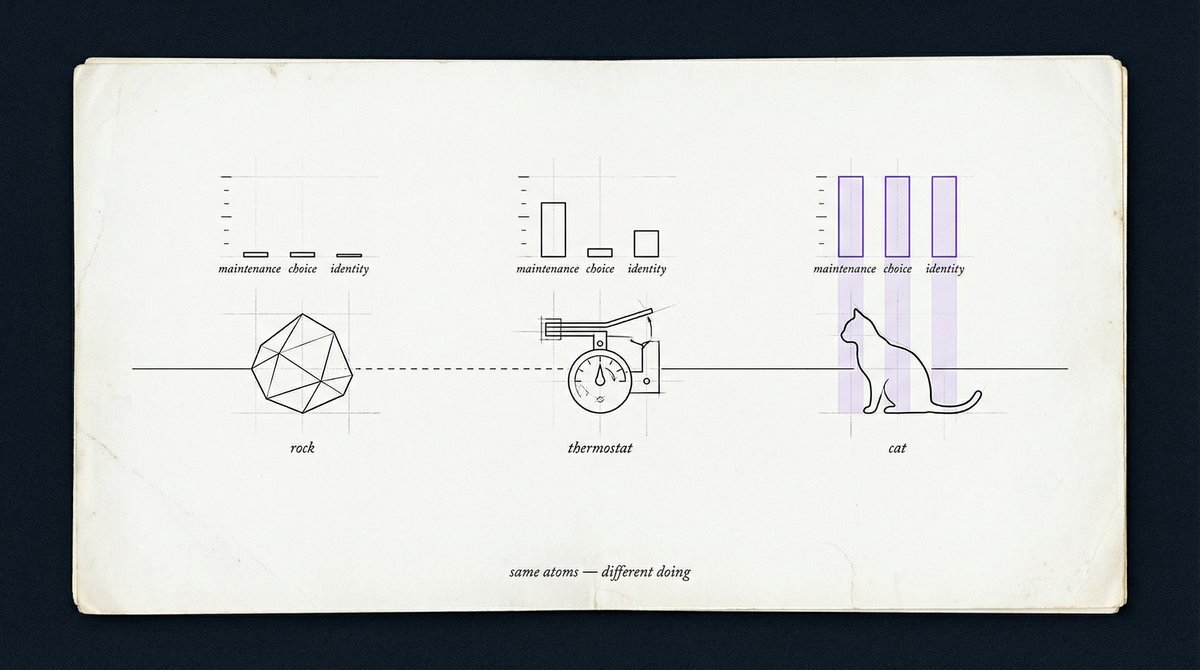

Once you see agency as three measurable quantities instead of a yes-or-no label, a spectrum appears.

A rock scores near zero on all three. It survives, but only because physics lets it. Chip it, and it stays chipped. It makes no choices. And it persists as "a rock" — a description so generic that it requires no maintenance to stay true.

A thermostat is slightly more interesting. It senses a deviation from a target and acts to correct it — it turns on a heater or triggers a cooling cycle. It has a sliver of choice: on or off. It maintains a target state. But it cannot rewrite its own target. If conditions change, it keeps pursuing the old goal until it breaks or someone reprograms it. It is an agent, barely — a one-dimensional agent with a single lever and a fixed instruction.

A cat is something else entirely. It maintains a complex internal chemistry against constant disruption. It makes choices that depend on context — stalking a mouse requires a different strategy than avoiding a dog, and the cat adjusts in real time. It persists as that specific cat, recognizable to its owner, to other cats, and to itself in ways we are still working out. And crucially, it can change its own behavior: a kitten learns to hunt, an indoor cat learns to open a cabinet. It rewrites its own operating rules when the old ones stop working.

The rock, the thermostat, and the cat are not three categories. They are three points on a continuum — a continuum you can measure, not just argue about.

The off switch

Here is the test that separates "happens to be stable" from "is an agent."

Researchers built small simulated worlds — grids where simple entities could move, consume resources, and repair themselves. Over time, these entities developed stable identities: describe one, describe it again, and you get the same entity back. They made choices that led to genuinely different futures. They survived by spending resources to fix internal damage.

Then the researchers turned the repair off. Same entities, same world, same physics — but no more self-maintenance.

Every signature of agency vanished. The stable identity dissolved — the entity stopped being a consistent, re-identifiable thing. The ability to reach different futures shrank, because there was no coherent "self" to steer with. Survival collapsed, because damage accumulated with nothing to fix it.

The maintenance was not supporting the agency. The maintenance was the agency. Take it away, and what remains is just stuff.

An agent is not something that wants. It is something that keeps itself together — and the keeping is what makes everything else possible.

Why the order of your actions matters

Here is something subtler. Think about chess.

A single move — pawn forward one square — does not look like much. But the order in which you make moves creates positions that no single move could reach. A knight-then-bishop sequence opens up a different board than bishop-then-knight. The game's richness comes not from the pieces but from the sequences.

The same turns out to be true for agency in general. In the emergence calculus, this is called route dependence: the path you take through your choices affects where you end up, in ways that cannot be reduced to the individual steps. A thermostat has one-step agency — it reacts to right now. A chess player has multi-step agency — the order of decisions compounds into futures that one-step reactions can never access.

This showed up clearly in the simulations. Entities with route-dependent actions — where the effect of move A followed by move B was different from move B followed by move A — could reach more distinguishable futures than entities without it. Not because they were smarter. Because the geometry of their action sequences gave them access to more of the world.

At one step, the two kinds of entities looked identical. At two steps and beyond, the route-dependent ones pulled ahead. Agency is not just about having choices. It is about having sequences of choices that compound.

Rewriting the rules

And then there is learning.

Not learning in the sense of memorizing facts. Learning in the sense of changing the rules by which you operate. A system that can rewrite its own internal physics — making its actions more reliable, more precise, more targeted — becomes measurably more agentic. Its choices produce sharper consequences. Its reach into the future grows.

In the simulations, entities were given a "skill" dial that controlled how reliably their actions translated into outcomes. At low skill, a command to move left might land you anywhere. At high skill, left means left. The result: every notch of skill produced a measurable increase in the entity's ability to reach distinct futures. Not because it knew more, but because its interface with the world had become a better translator of intention into consequence.

This is what learning actually is, underneath the everyday meaning. Not accumulating information. Rewriting the effective law that connects what you decide to what happens. A child learning to ride a bicycle is not storing data. The child is rewriting the mapping between "lean left" and "turn left" until the mapping becomes reliable. The child is becoming a better agent — literally, measurably, in the sense that more futures become reachable.

The part that gets personal

You are not a mind piloting a body. You are a maintained package — a system that actively holds itself together, that reaches into the world through a bounded interface, and that rewrites its own operating rules when the old ones stop working.

The Six Birds framework says that the word "agent" does not require consciousness, free will, or a soul. It requires three things you can measure. How large is the space of conditions in which you can keep yourself intact? How many distinguishable futures can your choices produce? How stable is your identity under repeated observation?

A rock has free stability, zero choices, and a generic identity. A thermostat has a small buffer of maintained stability, a binary choice, and a fixed instruction. A bacterium has active maintenance, context-sensitive choices, and a self-specific pattern it fights to preserve. And you — you have all of that at a scale so vast it feels like something else entirely. It feels like a mind. It feels like a self. It feels like free will.

Maybe it is all of those things. This framework does not rule that out. But it says something that those concepts alone could never say: it says how much. How much survival, how much choice, how much coherence. And it says that the answer, for every agent at every scale — from bacteria to bureaucracies — is always the same kind of answer. Not a philosophical stance. A measurement.

You are, right now, maintaining yourself. You are choosing what to read next. You are persisting as you. That is not a metaphor. It is the operational definition of what you are. A maintained package, throwing stones into the future — one choice at a time.

Read the research

To Throw a Stone with Six Birds: On Agents and Agenthood

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.