Close your eyes and point at something in the room. Your finger is aimed at a spot — a specific location in space. Now ask yourself: what is that spot? Not what is sitting there — a wall, a lamp, air. What is the spot itself made of? What makes "here" different from "there"?

Since Euclid, we have treated space as the stage — the fixed backdrop on which everything else plays out. First you draw the stage (points, lines, distances), then you fill it with actors (matter, forces, fields). The stage is always assumed to exist before the show begins.

But what if the stage is part of the show? What if points, distances, and the shape of space are not given in advance but built — by the same process that builds temperature, life, and time?

The blur test

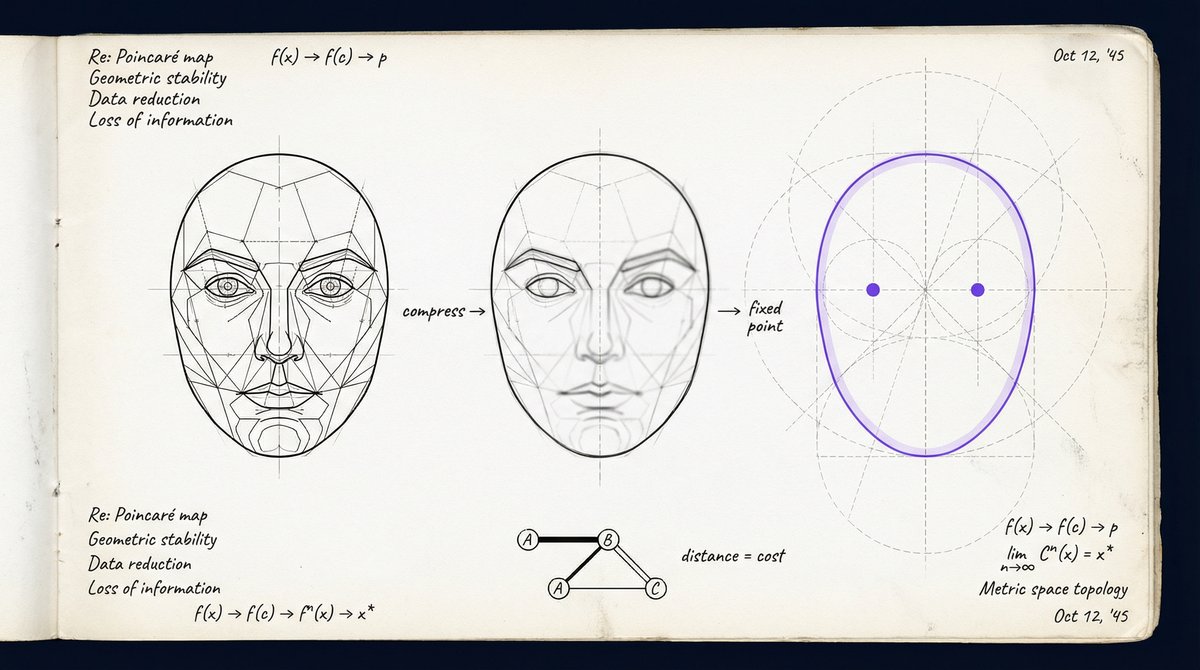

Start with a photograph — a sharp, high-resolution image of a face. Now blur it. Some features smear away immediately: a freckle, an eyelash, a strand of hair. Other features survive: the shape of the eyes, the line of the jaw.

Blur again. More details vanish. The individual features of the eyes are gone. But the oval of the face is still there. The basic layout — two dark spots above, one below — persists.

Blur again and again, as many times as you like. At some point, the image stops changing. What remains is a shape so stable that no further blurring can remove it. Those surviving features are not there because you drew them. They are there because they are the last things standing.

In the emergence calculus, this is exactly how a "point" in space is born. Take a system with an enormous number of micro-states — atoms jiggling, fields fluctuating, particles scattering — and compress it. Some macro-states survive the compression. Compress again, and the same ones survive. They are fixed points of the blurring process: descriptions so stable that they reproduce themselves no matter how many more times you squint.

A point is not where you start. A point is what survives.

How far is far?

Once you have points, you need distances. In school, distance is what you measure with a ruler — an external object laid against the gap between two things. But where did the ruler come from? Who decided that this much gap counts as "one centimeter"?

Think about a subway map instead. On a subway map, "distance" is not how many meters separate two stations. It is how easy it is to get from one to the other. Two stations on the same line, three stops apart, are "close" — even if they are physically far apart on the surface. Two stations on different lines, requiring a transfer and a long wait, are "far" — even if they are a block apart above ground.

In the emergent geometry framework, distance works like a subway map. The distance between two points is determined by the dynamics of the system itself — how easily the system can transition from one macro-state to another. If the transition is easy (high probability, low cost), the points are near. If the transition is hard (low probability, high cost), the points are far.

No ruler is needed. No external measuring stick. Distance is read off from the cost of moving — and "the cost of moving" is something the system's own dynamics provide for free.

Near means cheap to reach. Far means expensive. Distance is a price tag, not a number on a ruler.

Walking in a square and not coming home

Here is how you detect curvature without a single equation.

Stand in a field. Face north. Walk forward one hundred meters. Turn right. Walk forward one hundred meters. Turn right again. Walk one hundred meters. Turn right a third time. Walk one hundred meters. You have walked a square. You should be back where you started, facing north again.

On a flat surface, this works perfectly. But do the same thing on the surface of the Earth — start at the North Pole, walk to the equator, turn right, walk a quarter of the way around, turn right, walk back to the pole — and when you arrive, you are facing a different direction. You walked a "square" but you are rotated. The surface twisted you without you noticing.

That twist is curvature. And in the Six Birds framework, it is the same phenomenon that shows up everywhere else in the program: the order of operations matters. Walk east then north, and you end up in a different orientation than if you walk north then east. The gap between the two paths — the rotation you pick up by going around a loop — is a measurable number. On a flat surface, it is zero. On a curved surface, it is not.

Researchers tested this on packaged systems. They built two substrates — one flat (a grid), one curved (a sphere-like network) — and ran the loop test on both after packaging. On the flat substrate, the loop rotation clustered near zero. On the curved substrate, it shifted strongly upward. No coordinates were assumed. No metric tensor was imposed. Curvature was detected purely by walking in a loop and checking what changed.

The Pythagorean surprise

And then there is the result that sounds like it should be impossible.

The Pythagorean theorem — the one from school, the one about right triangles, the one that is 2,500 years old — is usually treated as a bedrock law of geometry. It is assumed. It is axiomatic. It is just true.

Except it turns out you can derive it from a random walk.

Start with a flat grid. Let a particle wander randomly — equal chance of going up, down, left, or right. After many steps, measure how far the particle has gone from where it started. Define "cost" as the negative logarithm of how likely that displacement is. In other words: rare moves are expensive, common moves are cheap.

Now check: does the cost of moving diagonally equal the sum of the costs of moving horizontally and vertically? Does c2 = a2 + b2?

It does. The Pythagorean theorem falls out — not as an axiom, not as a definition, but as a consequence of how independent random processes combine when you let them run long enough. When the horizontal and vertical wanderings are independent of each other, the squared costs add. Pythagoras emerges from probability.

As a control, the researchers tested a different kind of distance — one where you can only move along grid lines, never diagonally. The Pythagorean relationship failed, as expected. The test is discriminating: it finds the theorem when the conditions are right and rejects it when they are not.

Change the rules, change the shape

One more result, and it is the one that ties everything together.

Take the flat grid and block some directions. Say: you can move freely left and right, but moving up costs more. The grid is still the same grid. The points are still the same points. But the geometry warps. Distances in the blocked direction stretch. The shape of space deforms — continuously, measurably — in response to the constraints.

This matters because it provides a mechanism for dynamical geometry — the kind of thing general relativity requires. In Einstein's theory, matter tells space how to curve. In this framework, constraints tell the packaging process what geometry to produce. Change the constraints, and the shape of the resulting space changes with them. The geometry is not a fixed container. It is an output.

The part that gets personal

You navigate the world every day using a geometry you never built. You reach for a glass and your hand lands in the right place. You judge whether you can fit through a doorway without measuring. You catch a ball by predicting where it will be in half a second, using an internal model of space that you assembled from years of sensory experience.

That internal model is not a copy of some external grid. It is a compression — built from billions of interactions between your body and the world, refined by repetition, stabilized by use. The "points" in your spatial awareness are not mathematical abstractions. They are the macro-states that survived. The "distances" are not ruler measurements. They are transition costs — how hard it is, in your experience, to get from here to there.

Your sense of space is, in miniature, exactly the geometry this paper describes. Not a stage that was given to you, but a show you built — point by point, step by step, from the cost of moving through a world that never handed you a map.

Read the research

To Plot a Stone with Six Birds: A Geometry is A Theory

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.