You forgot to water the plant. It was on the windowsill for weeks, maybe months, slowly browning at the edges. One day you notice it is completely dry, stiff, gone. And you think: when exactly did it die?

Was it when the last cell stopped dividing? When the roots gave up pulling water? Or was it earlier — some quiet moment when a process you could not see wound down below a threshold, and everything after that was just coasting?

This question — what makes something alive — has been open since Aristotle. It is not a philosophical nicety. Entire fields depend on the answer. Doctors need it for end-of-life decisions. Astrobiologists need it to know what to look for on other planets. Origin-of-life researchers need it to know when their experiments have succeeded. And after twenty-five centuries of trying, nobody has a definition that works.

The checklist that never works

The standard approach is to list features. Life metabolizes. Life reproduces. Life maintains itself. Life evolves. If it does all four, it is alive.

But the list keeps letting in impostors.

A candle flame metabolizes. It eats wax and oxygen, produces heat and carbon dioxide, and responds to its surroundings — lean close and blow, and it dances. A crystal reproduces. Drop a seed crystal into a saturated solution and watch it copy its own lattice, atom by atom, until the jar is full. A thermostat maintains itself. It senses temperature, triggers a correction, and holds steady at a target. It has been self-regulating since before you were born.

None of these things are alive. Everyone agrees on that. But the checklist cannot explain why.

The usual fix is to add more items to the list. Life must do all of the above, and also contain DNA, and also be made of cells, and also have a boundary. But that is not a theory. It is a pile of observations shaped like a fence, and every time someone finds a counterexample, you add another rail. Viruses hop the fence no matter how high you build it.

Maybe the problem is not the list. Maybe the problem is the question. Instead of asking what is life, ask: what is a living thing doing that a non-living thing is not?

What if alive is something you do?

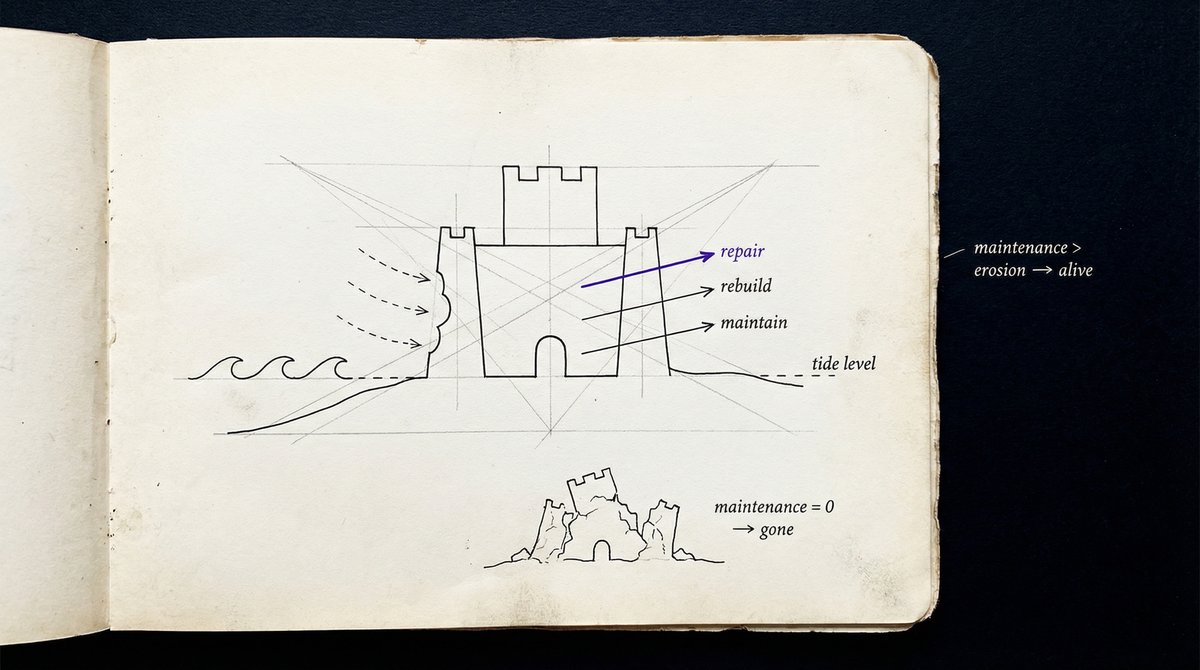

Think of a sandcastle on a beach. You built it this morning. It has towers, a moat, a little flag on top. It is intricate and specific — there is no other castle quite like it on the whole coast.

Now the tide is coming in. Every wave eats a little more. If you sit there and rebuild — patching the walls, re-digging the moat, replacing the flag — the castle survives. Walk away, and it is gone within the hour. Same sand, same beach, same physics. The only difference is whether someone is doing the upkeep.

A living cell is a sandcastle that rebuilds itself.

Its DNA gets damaged by radiation, by copying errors, by ordinary chemistry going wrong — and a repair crew finds the break and patches it, thousands of times a day. Its proteins unfold in the heat — and chaperone molecules refold them. Its membrane leaks ions in the wrong direction — and pumps spend energy to push them back. Every second, in every cell of your body, things are falling apart and being put back together.

That upkeep is not a side effect of being alive. According to a framework called the emergence calculus, that upkeep is what being alive means. A living system is one that spends energy to keep its own description stable. Stop the spending, and the description falls apart — the way the sandcastle dissolves when you walk away.

Life is not a substance you are made of. It is a bill you keep paying. Miss enough payments, and the pattern dissolves.

Three things on a beach

This way of thinking turns a yes-or-no question into a spectrum. Consider three things you might find at the shore.

A pebble. It has a stable description — a shape, a color, a density that barely changes from year to year. But it is not paying anything for that stability. The atoms settled into a low-energy arrangement a long time ago and stayed there. The pebble is stable for free. Ordered, but not alive.

A flame on a piece of driftwood. It is busy — consuming fuel, producing heat, flickering in the wind. It is far from settled. But it is not maintaining anything specific. Snuff it out and relight it, and you get roughly the same flame. There is no particular pattern it is fighting to preserve. Active, but not alive.

A crab. It is both specific and maintained. Its shell is a particular shape. Its nervous system fires in particular patterns. Its blood chemistry holds within particular bounds. And all of this costs energy — energy that the crab spends every second, scavenging food and burning it to keep the whole arrangement from falling apart. It is paying a continuous maintenance bill to stay itself.

The pebble is free stability. The flame is aimless activity. The crab is maintained stability. That intersection — a complex, specific pattern that persists only because something is actively working to keep it there — is what we recognize as life.

The off switch

Here is the test that makes this more than a nice metaphor.

Researchers built two very different computer simulations — one based on particles bumping into each other, one based on networks of nodes firing and rewiring. Both were given energy budgets and internal repair mechanisms. Over time, both developed patterns that looked strikingly life-like: stable internal structures, recurring motifs, consistent responses to the environment.

But looking life-like is not enough. Clouds look like faces sometimes. You need a way to check whether the pattern is real or just a coincidence.

So they ran the experiment again with one change: they turned the maintenance off. Same starting conditions, same physics, same everything — except the repair mechanisms were disabled. The energy budget was cut.

Every life-like signature vanished.

The stable structures dissolved. The recurring motifs scrambled into noise. The consistent responses became random. It was not a gradual decline — it was a clean disappearance. The maintenance was not decorating the pattern. The maintenance was the pattern. Remove the cause, and the effect is gone.

This is a powerful result. It rules out the possibility that the simulations just happened to look alive because of a lucky setup. The life-like behavior was caused by the active upkeep — and by nothing else.

A dial, not a line

If life is maintenance, then "alive" is not a line you cross. It is a dial. And the dial can read anywhere from zero to very high.

Think about viruses. Outside a host cell, a virus is a crystal — a beautiful, specific arrangement that is stable for free. It does not eat, does not repair itself, does not spend any energy. The maintenance dial reads zero. Inside a host cell, the virus hijacks the cell's own maintenance budget to copy itself. Now the dial has moved — but it is the cell's dial, not the virus's.

Is a virus alive? The question dissolves. It has a maintenance budget that changes with context. Outside: zero. Inside: borrowed. The answer is not yes or no. It is a number.

The same logic applies everywhere the old definitions struggled. Prions — misfolded proteins that spread by converting other proteins — have no DNA, no cells, no metabolism in the traditional sense. But they do maintain a pattern by actively reshaping their surroundings. The dial is not at zero. It is low, but it is not zero.

A frozen embryo has its maintenance dial paused — nearly zero — and yet we call it alive because we know the dial can be turned back up. A brain-dead patient on a ventilator has mechanical maintenance but no self-directed maintenance. The Six Birds framework does not hand you an answer to these cases. It hands you a measurement, and lets the measurement do the work that definitions never could.

What this means for the search

If you are looking for life on Mars or Europa, you have a problem. Every detector we have ever built assumes Earth-like chemistry. It looks for water, carbon, specific gases. But if life is maintenance rather than a substance, then it could run on chemistry we have never seen — and our detectors would miss it entirely.

A maintenance-based detector would work differently. Instead of asking what is this made of, it would ask: is something here spending energy to stay organized? That is a question you can ask regardless of the chemistry. It works on carbon life, silicon life, or anything else that might be out there paying its own bills.

The same idea reshapes origin-of-life research. Instead of arguing about which molecule came first — RNA or protein, metabolism or membrane — you can ask a simpler question: at what point did a prebiotic chemical system start spending energy to keep its own pattern stable? That is the moment the maintenance dial moved off zero. That is where life began — not with a molecule, but with an activity.

The part that gets personal

Your stomach lining replaces itself every few days. Your red blood cells last about four months. Your skeleton rebuilds over the course of a decade. Almost none of the atoms in your body right now were there ten years ago.

You are not the same stuff you were made of. You are the pattern — and the pattern persists only because trillions of tiny maintenance jobs are being done every second, without your awareness, without your permission, without a break since the day you were conceived.

That is what it means to be alive. Not to be made of special ingredients. Not to have crossed some threshold into a magic category. To be engaged in the continuous, expensive, never-finished work of staying yourself.

The houseplant on the windowsill stopped doing that work. Not all at once — gradually, cell by cell, as the water ran out and the repair crews shut down one by one. There was no single moment of death. There was a maintenance budget that slowly dropped to zero.

Yours has not. Not yet. Every breath you take is a payment. Every meal is a deposit. You are a pattern that has been maintained without interruption for your entire life — a sandcastle that has been rebuilding itself since before you could remember, in a tide that never stops.

Read the research

To Wake a Stone with Six Birds: A Life is A Theory

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.