Try this experiment. Pick up the nearest object — a mug, a pen, your phone. Now ask yourself: where does its hardness come from?

Not what causes it. Where does the concept come from? Zoom into the atoms, and you will not find hardness there. An atom is not hard or soft. It is a cloud of probability. Zoom further into quarks and gluons, and the idea of hardness becomes absurd — like asking what color a number is.

Yet here you are, holding something hard. The hardness is real. You can knock on it. You can break a window with it. It just does not exist in the ingredients that make the object up.

This is not a philosophical puzzle. It is the central unsolved problem of science: how do new concepts appear when you change scale?

The gap nobody talks about

Science has a standard story about this. It goes like this: the big picture is "just" the small picture, summarized. Temperature is "just" the average speed of molecules. Pressure is "just" molecules bouncing off walls. Life is "just" chemistry. Mind is "just" neurons firing.

The word "just" is doing a lot of heavy lifting in that story. Because if temperature is just an average, then it should be possible — at least in principle — to take the average apart and recover the original pieces. You should be able to go back.

But you can't. Take the temperature of a room — say, 22 degrees. Now try to figure out what each individual molecule was doing. You cannot. Not because you lack computing power, but because the information is gone. Trillions of different arrangements of molecules all give you the same 22 degrees. The summary destroyed its own trail.

So temperature is not a shorthand. It is not an abbreviation you can undo. It is something else — something that was born in the act of stepping back and looking at the big picture. Something that only exists at that bigger scale.

This is the crack in the foundation. And once you see it, you see it everywhere.

What the crack looks like from above

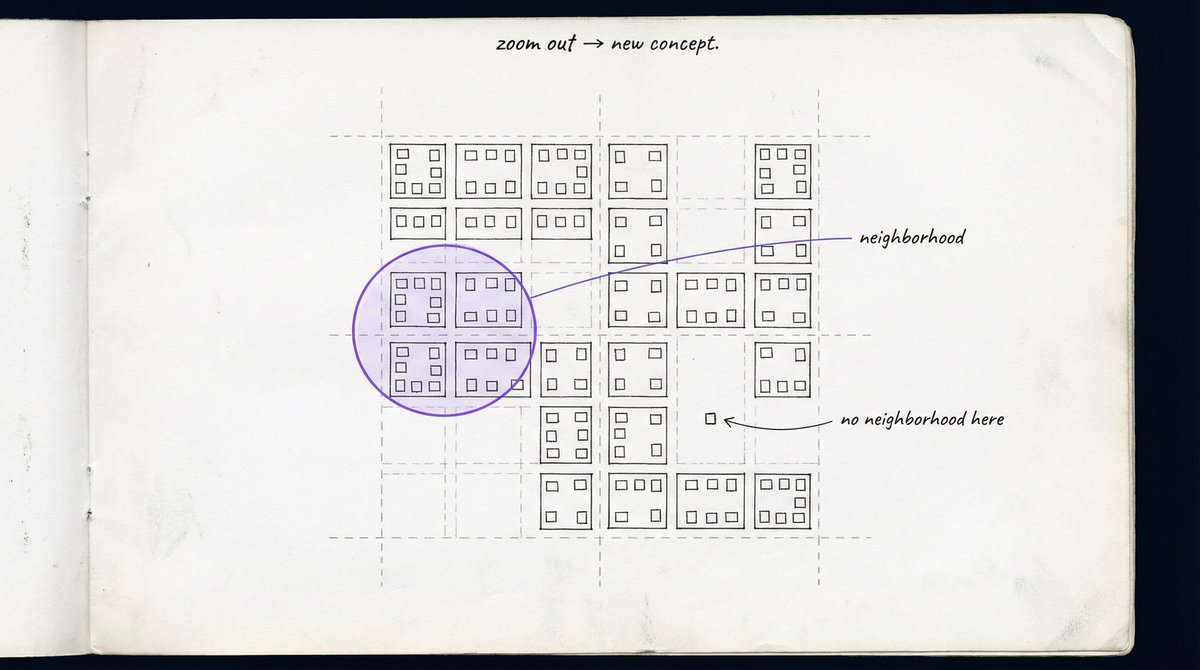

Think of a city seen from an airplane. You can see neighborhoods — residential here, industrial there, a park in between. Those neighborhoods are real. City planners make decisions about them. Property values depend on them. People live their lives inside them.

But if you zoom in to a single house, "neighborhood" vanishes. A house does not contain its neighborhood any more than a molecule contains temperature. The neighborhood appears only from above, when you look at enough houses at once and something clicks into place: these go together, those don't.

Now here is the question that gets interesting. That click — that moment when a pattern locks in and becomes a stable thing you can point at and name — is it the same kind of click every time? Does it work the same way when molecules become temperature, when neurons become a thought, when stars become a galaxy?

The emergence calculus — a framework called Six Birds — says yes. And it says something more: the click always involves exactly six steps.

Six things that happen every time

Not six ingredients or six forces. Six things that happen, in a recognizable order, whenever one level of reality gives rise to another.

Think of them through the city analogy.

First, there is a translation. The raw data — every house, every yard, every crack in the sidewalk — gets compressed into a coarser picture. Streets become lines. Blocks become shapes. This is the act of stepping back.

Second, a gate closes. The coarser picture cannot see everything the finer picture could see. From the airplane, you can tell that a neighborhood is residential, but you cannot tell what anyone had for breakfast. That information is locked out. This is not a failure — it is how the new level gets to be its own thing.

Third, the order you step back matters. Group houses by street first and then by income, and you get one picture of the city. Group by income first and then by street, and you might get a different picture. The path you take through the zooming-out process affects what you end up with. This is not a bug. It means the bigger picture carries a trace of how it was made.

Fourth, the problem breaks into pieces. You do not understand a city all at once. You understand the transit system, the economy, the demographics, the geography — semi-independent chunks that you can think about separately before putting them back together.

Fifth — and this is the big one — the picture locks. At some point, the pattern stabilizes. Zoom out a little more and the neighborhoods do not change. The picture survives further blurring. It has become a fixed point — something that reproduces itself no matter how many more times you squint. This is the moment a new object is born. Mathematicians call it a closure.

Sixth, there is an audit. Every time you zoom out, you lose detail. The audit is the precise record of what was lost — how much information was thrown away, and whether the new picture is honestly representing what lies beneath. Without the audit, you are just making things up. With the audit, you can check.

Why the fifth step changes everything

The locking step — the closure — is where the magic happens. It is the difference between a blurry photo and a face.

Think about what it means for a pattern to survive further blurring. It means the pattern is not an artifact of how closely you are looking. It is not a trick of resolution. It is there — in the same way that a face in a crowd is there, even though no single pixel contains it.

And here is what the mathematics shows: when the locking happens, the new object almost always contains concepts that cannot be translated back into the language of the level below. Not "we haven't figured out how to translate them yet." Cannot, in principle. The math proves it.

This is a theorem, not an opinion. It says that when you zoom out from a sufficiently rich world, the big-picture concepts you get are overwhelmingly new. They are not rearrangements of small-picture concepts. They are words that only exist in the big-picture dictionary.

Temperature is one of those words. So is "alive." So is "Tuesday." So — if the framework is right — is everything stable you have ever encountered at any scale.

The universe is not a tower of abbreviations. It is a tower of inventions — each level coining words that the level below cannot even pronounce.

Why should you believe any of this?

Good question. Grand claims about reality usually come with grand hand-waving. This one comes with an audit — literally. The sixth step in the framework is a built-in check. For any claimed new object, you can compute a number that tells you whether it is genuinely stable or just noise. If the number is bad, the object fails. No arguing, no taste, no philosophy. Just math.

The same framework has been tested across very different domains — from the behavior of quantum particles to the expansion of the universe, from what makes something alive to what makes something count as a point in space. In each case, the same six steps appear, the same audits can be run, and the same kind of locking occurs. The details are wildly different, but the skeleton is the same.

That is either a coincidence or a clue. The rest of this series follows the clue.

The part that gets personal

If this picture is right, then everything you interact with — every object, every idea, every relationship — is a locked pattern that some zooming-out process created. Including you.

Your sense of being a single person, with a name and memories and a continuous thread of experience — none of that exists at the level of your atoms. Your atoms do not know your name. They were in a star once. They will be in something else later. "You" is a word that only exists at the right scale, the way "neighborhood" only exists from an airplane.

But that does not make you less real. It makes you a different kind of real — the kind that is written by the universe rather than found in it. A pattern so stable it forgot it was a pattern.

The dictionary is not finished. New entries are being written right now, at scales we do not yet have instruments to see. The emergence calculus is, at its core, a way of reading the dictionary — checking which entries are genuine and which are noise, page by page, scale by scale.

Read the research

Six Birds: Foundations of Emergence Calculus

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.