In 1998, two teams of astronomers pointed their telescopes at distant supernovae and discovered something that should not have been happening. The expansion of the universe was speeding up. Galaxies were not just drifting apart — they were accelerating away from each other, as if something were pushing the cosmos apart from within.

Nobody knew what that something was. So they gave it a name — "dark energy" — and moved on. Today, dark energy is said to make up 68% of the total energy content of the universe. It has no confirmed particle. No laboratory signature. No theoretical consensus on what it actually is. It is, in the most honest sense, a placeholder: a term added to the equations to make the numbers work.

What if there is nothing to find? What if dark energy is not a substance at all, but a side effect of the way we do the math?

The problem with smoothing a lumpy thing

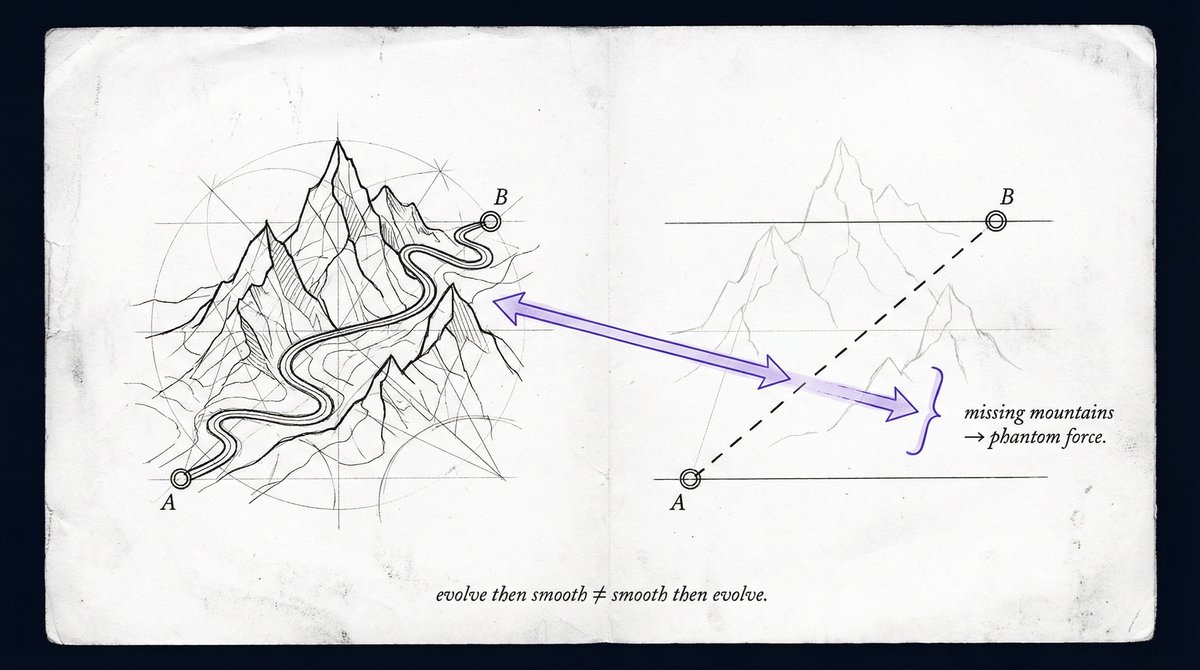

Imagine you have a detailed topographic map of a mountain range. Every peak, every valley, every ridge is marked. Now someone asks you to summarize the terrain on a flat road map — just distances between towns, no elevation.

You flatten the map. You replace the winding mountain roads with straight lines. And immediately, the distances are wrong. The straight-line distance between two towns on opposite sides of a mountain is shorter than the actual road. The flat map says twenty kilometers; the real drive is forty.

If you did not know the mountains were there, you might conclude that something mysterious was stretching the roads. You would need an extra term in your equations — a "road-stretching force" — to explain why the flat model's predictions do not match reality.

But there is no road-stretching force. There are just mountains you threw away when you flattened the map. The "force" is a correction for the information you lost.

This is the dark energy hypothesis of the emergence calculus. The real universe is lumpy. Galaxies clump together into filaments and walls. Between them lie vast, nearly empty voids. The density of matter varies enormously from place to place. But when cosmologists model the universe, they use equations that describe a perfectly smooth, uniform cosmos. The lumpy reality is flattened into a smooth approximation — and the flattening has a cost.

Evolve then smooth, or smooth then evolve

Here is where the cost becomes specific and measurable.

There are two ways to predict what the universe will look like in a billion years. You can take the lumpy universe, evolve it forward in time with all its detail intact, and then smooth the result into a simple model. Or you can smooth the universe first, then evolve the smooth model forward.

If the universe obeyed simple, linear laws, the two paths would give the same answer. But gravity is not linear. Dense regions pull harder. Voids expand faster. The details interact with each other in ways that do not average out cleanly. So the two paths give different answers.

Evolve then smooth: one result. Smooth then evolve: a different result. The gap between them is not zero. And it behaves, in the equations, exactly like a cosmological constant — exactly like dark energy.

The gap between "evolve then smooth" and "smooth then evolve" has to go somewhere. In cosmology, it goes into what we call dark energy.

Building a universe with nothing in it

Here is the test that makes this more than speculation.

Researchers built a synthetic universe — a simulation — with zero dark energy. No cosmological constant. No mysterious substance. Just matter: lumpy, gravitationally clumping, inhomogeneous matter. This universe is the ground truth, and in it, there is genuinely nothing to detect.

Then they analyzed this dark-energy-free universe using the same tools that real astronomers use on real data. The same smooth-model fitting. The same parameter extraction. The same pipeline that produced the headlines in 1998.

The tools "discovered" dark energy. They reported a value of roughly 0.6 for the dark energy fraction — despite the fact that the underlying universe contained exactly zero. The smooth model was forced to invent a cosmological constant to compensate for the information lost in the smoothing. The tools were not wrong. They were doing the best they could with a model that assumes the universe is smooth. But the price of that assumption was a phantom substance.

The observed value in our actual universe is about 0.68. The synthetic test does not claim this match is proof. But the mechanism is quantitatively in the right ballpark — not a negligible correction, not off by orders of magnitude, but a substantial fraction of the total energy budget.

The fingerprint test

If dark energy is a real substance — a uniform field filling all of space — then every way of measuring it should give the same answer. Look at distant supernovae: one value. Look at the pattern of sound waves frozen into the cosmic microwave background: the same value. Look at how galaxies cluster: the same value again. A real substance does not care how you measure it.

But if dark energy is an artifact of smoothing, the probes should disagree. Different telescopes and different techniques look at different scales and different distances. Each one smooths a different part of the lumpy universe. If the smoothing is the source of the "dark energy," each probe should pick up a slightly different artifact — and the pattern of disagreement should follow a specific, predictable structure.

Researchers ran this test against real observational data — supernovae, baryon acoustic oscillations, gravitational lensing, galaxy clustering. They fit a smooth model to one type of observation and then asked: does that model correctly predict the other observations?

It does not. The probes show tension — systematic disagreement that follows the pattern expected from a smoothing artifact. The disagreement is not random noise. It has structure. And that structure is exactly the fingerprint you would expect if the "dark energy" were coming from the gap between the lumpy universe and its smooth approximation.

The same gap, everywhere

This gap — between "do something detailed, then summarize" and "summarize first, then do something with the summary" — appears in every paper in the Six Birds program. In quantum mechanics, it shows up when the order of measurements changes the outcome. In geometry, it shows up as curvature: walk in a loop and find that you have rotated. In time, it shows up as the impossibility of a single global clock.

In cosmology, it shows up as dark energy. The same structural gap — the same noncommuting operations — that generates curvature in a lattice model generates an apparent cosmological constant in the smoothed universe. These are not analogies. They are instances of one phenomenon, diagnosed by one tool, across every domain the framework has been applied to.

The part that gets personal

Every model you carry in your head is a smoothed version of something lumpier. Your understanding of your job, your family, your finances — all of it is a compression that throws away enormous amounts of detail. And every compression has a cost. Every time you "smooth" a messy situation into a simple story, you introduce a gap between the simple story and what actually happens next.

Sometimes you notice the gap and call it bad luck, or mystery, or a force you cannot see. The relationship that seemed fine but fell apart. The project that was "on track" but failed. The budget that should have worked but did not. Maybe there is a mysterious force. Or maybe you smoothed a lumpy thing and forgot that smoothing has a price.

Sixty-eight percent of the universe might be that kind of mistake. A rounding error so large it was mistaken for a discovery. The emergence calculus cannot yet prove this — nobody can, not yet. But it provides the tools to find out: a way to measure the cost of smoothing, check whether different measurements agree, and tell the difference between a substance and a side effect.

The most dramatic discovery in modern cosmology — that the expansion of the universe is accelerating — might not be a discovery about a new substance at all. It might be a discovery about the price of approximation. About what happens when you flatten a mountain range and then wonder why the distances seem wrong.

Read the research

A Six Birds' Eye View of Dark Energy

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.