You dropped a mug this morning. It hit the kitchen floor and shattered into a dozen pieces. You swept them up, tossed them in the bin, and made coffee in a different mug.

Now play that scene backward. A dozen shards leap out of the trash, sail through the air, snap together, and land intact in your hand. You know this is ridiculous. But why do you know?

Not because the laws of physics forbid it. Newton's laws work perfectly well in reverse. The equations of quantum mechanics are symmetric in time. If you filmed a single atom bouncing off another atom and played the clip backward, no physicist could tell which version was the original. At the level of individual particles, there is no arrow. Forward looks exactly like backward.

And yet mugs shatter. Eggs break. Ice melts. The universe clearly has a direction. So where does the one-way feeling come from, if it is not in the fundamental laws?

Three things wearing one name

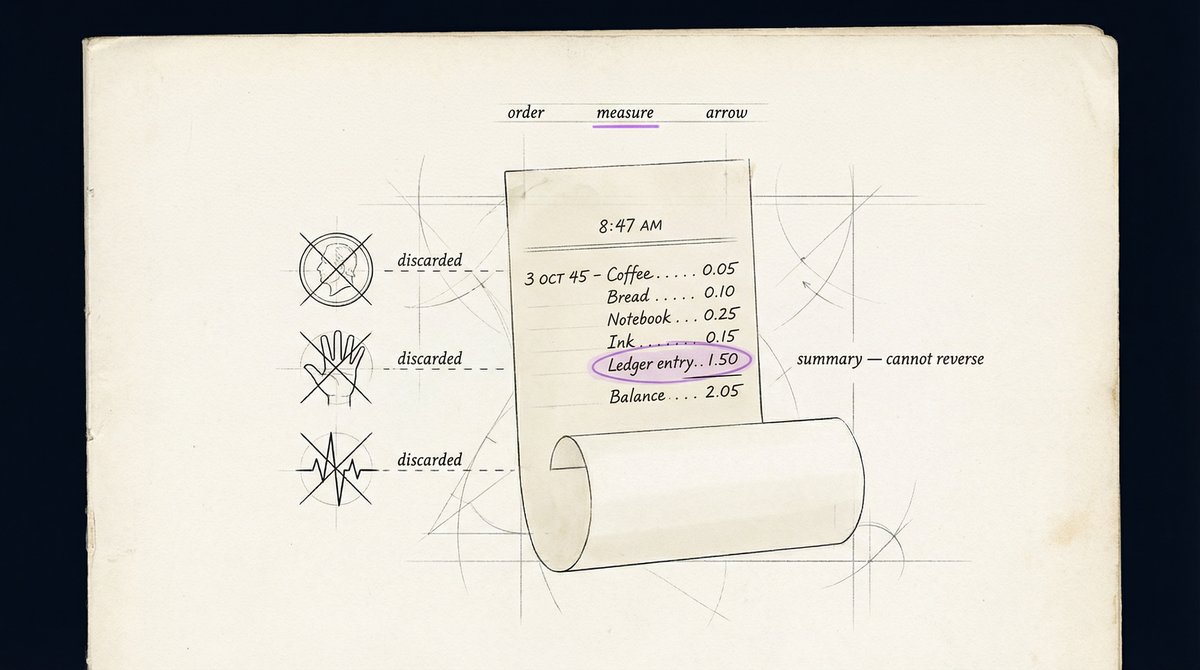

We talk about "time" as if it were one thing. A river that flows from past to future. A clock that ticks in the background. An arrow that points in one direction.

But those are three separate ideas, and they come from three different places.

Order is about sequence. What happened before what. You dropped the mug, then it hit the floor. Not the other way around. Something in the world has to provide this "before" and "after" — and it is not as automatic as it sounds. In a world with no records and no memory, there is no before. There is just stuff happening.

Measure is about duration. How long between two events. This requires a clock — something that ticks reliably enough to count. A pendulum, a quartz crystal, a heartbeat. But a clock is a thing, not a backdrop. It is a device that someone built or that nature assembled, and it takes work to keep it running.

Arrow is about direction. Why yesterday is different from tomorrow. Why you can remember breakfast but not dinner tonight. Why the mug shatters but never reassembles.

We usually bundle all three into the word "time" and move on. But what if unbundling them is the whole point? What if order, measure, and arrow each have to be manufactured — and each one costs something?

The receipt that explains everything

Think about a cash register.

You buy a coffee. The register records the transaction: one coffee, three dollars, 8:47 AM. It prints a receipt. The receipt is a one-way document. It proves that something happened, but you cannot use it to un-happen the transaction. The coffee is already being drunk. The money is already in the till. The receipt just says: this occurred, and it cannot un-occur.

Why can it not be reversed? Because making the receipt destroyed information. The register does not record which particular coins you used, or the angle of your hand as you paid, or the barista's heartbeat at the moment of the pour. All of that detail was thrown away. The receipt is a summary, and summaries are lossy. To reconstruct the exact original transaction from the receipt alone, you would need information that no longer exists.

Now go back to the mug. When it shattered, information about the exact arrangement of every atom in the mug was scattered across the floor, the air, and the heat of the impact. A receipt was printed — "mug is broken" — and the fine detail was discarded. To reassemble the mug, you would need that detail back. But the receipt does not contain it. It cannot contain it. That is what makes it a receipt.

The arrow of time is not a law written into the universe. It is a side effect of bookkeeping. Every time a system summarizes fine detail into a coarser record, it prints a receipt and throws away the original. You cannot return what you cannot reconstruct.

Your clock is a machine that needs feeding

The arrow explains direction. But what about duration — the ticking, the counting, the sense of how much time has passed?

A clock is not a window onto some background flow of time. A clock is a machine. It has to keep doing the same thing over and over — swinging, vibrating, pulsing — and it has to do it reliably enough that you can count the repetitions.

That reliability costs energy. A grandfather clock needs winding. A quartz watch needs a battery. An atomic clock needs a laboratory. Even your biological clock — the circadian rhythm that tells you when to sleep — needs food and light to stay calibrated. Without maintenance, every clock drifts, stutters, and eventually stops.

In the emergence calculus, a clock is a maintained package. It is the same kind of thing as a living cell or an agent: a pattern that persists only because something is actively working to keep it stable. Cut the maintenance budget and the ticking falls apart — not because the clock "broke" in some dramatic way, but because reliability is a service, and the service requires payment.

Researchers tested this in simulations. They built simple systems with an internal oscillator — a proto-clock — and gave them adjustable maintenance budgets. With a high budget, the clock ticked cleanly: low drift, few failures, stable intervals. Cut the budget, and drift crept in. Cut it further, and the ticking dissolved into noise. The same physics, the same setup — but without the upkeep, the system lost the ability to measure its own duration.

The off switch

Here is the test that makes this more than a thought experiment.

Take the maintenance away. Do not change the system, do not change the physics, do not touch the initial conditions. Just turn off the repair mechanism — the thing that snaps the oscillator back when it drifts, the thing that spends energy to keep the ticking on track.

Every time-like signature disappears. The arrow collapses: without records being actively maintained, there is nothing to distinguish forward from backward. The clock fails: without repair, the oscillator wanders into noise and the ticks become meaningless. The ordering dissolves: without a stable sequence to anchor events, "before" and "after" lose their grip.

The maintenance was not supporting time. The maintenance was time. Order, measure, and arrow were all being manufactured by the same process — the active, expensive, ongoing work of keeping records stable and clocks ticking. Turn off the factory, and the product is gone.

Why there is no master clock

Here is the part that gets strange.

Relativity already taught us that time can run at different speeds depending on how fast you are moving or how strong the gravity is near you. But the Six Birds framework goes somewhere further. It says that different ways of summarizing the same system can produce different time orderings — not because of motion or gravity, but because the act of summarizing itself is path-dependent.

Think of it this way. Two accountants are keeping books on the same company. They use different categories, different rounding rules, different fiscal calendars. Each set of books is internally consistent — every transaction balances. But when they try to merge their books into a single master ledger, the numbers do not add up. The discrepancy is small but real. No single set of books can represent what both accountants were tracking.

The same thing happens with time. Researchers measured the "time translation" between different summary protocols — different ways of coarse-graining the same underlying system. Each protocol produced a valid local timeline. But when they chained the translations in a loop — protocol A to B, B to C, C back to A — they did not land back where they started. There was a gap. A measurable, nonzero gap.

That gap means there is no master clock. No single timeline that all protocols agree on. Time is local to the summary you are using, and different summaries can disagree in ways that cannot be reconciled.

The part that gets personal

Every moment you remember is a receipt.

The neural pattern that encodes "I had coffee this morning" was created by a process that threw away almost everything about that moment. The exact temperature of the cup, the pattern of steam, the sound of the radio in the background — nearly all of it is gone. What remains is a summary: coffee, morning, kitchen. A handful of words compressed from a billion sensory details.

You cannot go back to that moment. Not because time is a river flowing in one direction, but because the receipt does not contain enough information to reconstruct what it summarized. The original transaction is over. The goods have been consumed. You are left with the record, and the record is one-way.

That is what time is. Not a river. Not a stage on which things happen. A stack of receipts — printed by the act of living, paid for by the energy of staying organized, and unreturnable because the fine print was thrown away the moment it was written.

Your body is printing receipts right now. Your cells are recording damage and repair. Your brain is compressing this paragraph into a memory that will keep some of these words and lose the rest. Each receipt adds to the stack. Each one points in one direction. And the stack is your experience of time passing — not because the universe has a clock, but because you are a system that never stops summarizing, never stops discarding, and never gets the originals back.

Read the research

To Notch a Stone with Six Birds: Time as a Theory Artifact

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.