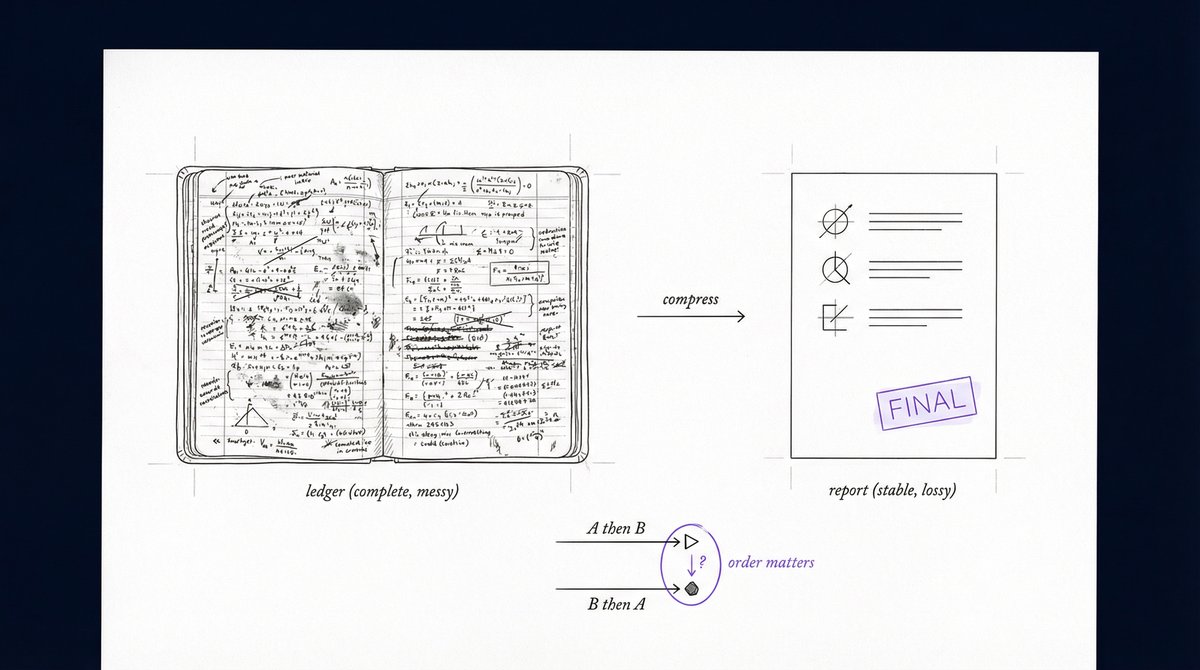

Imagine a small shop — the kind with a handwritten ledger in the back room. Every sale, every return, every expense, scrawled in a thick notebook. The ledger is complete. Everything that happened is in there. But it is a mess — thousands of entries, no particular order, corrections in the margins.

Now an accountant arrives to prepare the annual report. She reads the ledger, sorts transactions into categories, adds them up, and produces a clean one-page summary. Revenue, expenses, profit. Done.

Two things are true about that summary. First, it is stable: run the same process again and you get the same report. Second, it is not the business. It is a record — a compressed description that kept some information and threw the rest away.

This distinction — between what actually happened and the record you made of it — turns out to be the key to the strangest theory in all of physics.

Two things wearing one name

Quantum mechanics has been baffling people for a hundred years. A particle passes through two slits at once. A cat is alive and dead until someone opens the box. A measurement on one side of the galaxy seems to instantaneously affect a particle on the other side.

Physicists have tried everything to explain this: parallel universes, hidden variables, consciousness causing reality to snap into place. None of it has settled the debate.

The emergence calculus offers a different diagnosis. The weirdness is not in nature. It is in the bookkeeping. Specifically, quantum mechanics uses a single mathematical object — the "quantum state" — to do two completely different jobs.

Job one: describe what nature is doing. Particles scatter, fields ripple, things evolve. This is the ledger — the full, detailed, messy story of what is actually happening.

Job two: describe what you can record. When you measure something, you form a stable description — "the particle was here," "the spin was up." This is the report — the clean, compressed summary that throws away detail you cannot access.

When you confuse the ledger with the report — when you treat the act of making a record as if it were a physical event happening to the particle — you get collapse, spooky action, and a dead-and-alive cat. Separate them, and the strangeness dissolves.

The report that only needs to be filed once

The most notorious mystery in quantum mechanics is "wave function collapse." Before you measure a particle, it exists in a blur of possibilities — it could be here or there, spinning this way or that. The moment you measure it, the blur snaps into a single definite answer. Where did the other possibilities go? What caused the snap?

Physicists have argued about this for a century. Is it a physical event? A change in your knowledge? A branching of universes?

Here is the bookkeeping answer: collapse is what happens when you file the report. The accountant reads the ledger, produces a summary, and stamps it "FINAL." Now stamp it again. Nothing changes. The report was already filed. Stamping it a second time does not create a new report. It just confirms the old one.

That is all collapse is. You formed a record — a stable summary of a messy quantum system — and the record, once formed, does not change when you form it again. No snap. No mystery. No parallel universes. Just a filing process that stabilizes on the first pass.

Collapse is not something that happens to the particle. It is something that happens to the record. The report crystallizes, and once it has crystallized, filing it again changes nothing.

Two accountants, one ledger

Here is where it gets interesting.

Suppose two accountants are asked to summarize the same messy ledger. Accountant A sorts transactions by department. Accountant B sorts by client. Each produces a clean, stable report. But the two reports look different — different line items, different totals, different stories about what the business did.

Now here is the catch. If accountant A files her report first, and then accountant B tries to produce his report from A's summary, he gets one answer. But if B files first and A works from B's summary, she gets a different answer. The order matters. A-then-B does not equal B-then-A.

Why? Because each report throws away different details. Once those details are gone, the second accountant is working from an incomplete record. And which details are missing depends on who went first.

This is exactly what happens in quantum mechanics. Measuring a particle's position is one way of filing a report. Measuring its momentum is another. File the position report first, then the momentum report, and you get one result. Reverse the order and you get a different result. The order of measurements changes the outcome — not because nature is being coy, but because each measurement throws away different information, and the information you lose first determines what is available second.

This is the same gap — between "do A then B" and "do B then A" — that shows up in every paper in the Six Birds program. In cosmology, it produces what looks like dark energy. In geometry, it produces curvature. In quantum mechanics, it produces the strange dependence of results on which measurement you perform first.

The doors no one was watching

The double-slit experiment is the most famous puzzle in quantum mechanics. A particle approaches a barrier with two openings. Fire many particles, one at a time, and they build up a striped pattern on the detector screen — bright bands where particles cluster, dark bands where almost none arrive. The stripes are an interference pattern, the kind of thing waves make.

But place a detector at one of the slits — a guard who writes down which opening each particle used — and the pattern vanishes. The stripes disappear. The particles now hit the screen in two plain blobs, one behind each slit.

The guard did not push anything. The guard did not block anything. The guard just wrote something down. And the act of writing changed the result.

In the bookkeeping picture, this makes perfect sense. When no record of which slit was used is formed — when no report is filed — the particle's two possible paths remain in the ledger as unsummarized detail. That unsummarized detail produces the interference pattern. The stripes are the signature of information that has not yet been compressed into a record.

The moment a record forms — "the particle went through slit A" — the unsummarized detail is gone. The report has been filed. The interference pattern, which depended on that detail, disappears with it.

And here is the clincher. In certain experiments, you can erase the which-slit record before it becomes permanent — before the report is stamped and filed. When you do, the interference pattern comes back. The information was not destroyed. It was temporarily hidden by a report that had not yet been finalized. Shred the draft, and the original detail reappears.

The cat was never both

Schrödinger's cat — the thought experiment where a cat is supposedly alive and dead at the same time until someone opens the box — has been tormenting people since 1935.

Here is the bookkeeping answer.

The ledger — the complete, detailed quantum description of the cat, the box, the radioactive atom, and the entire environment — is consistent and well-defined. There is no contradiction at that level. The full description is doing its job perfectly.

The report — the summary you get when you open the box and form a record — says: cat alive, or cat dead. One or the other. Not both. This report is also consistent and well-defined. It is the stable summary that survived the filing process.

These are two descriptions at two different levels, and they are both correct at the same time. The ledger does not need to match the report, any more than the handwritten notebook needs to match the clean one-page annual summary. They are tracking different things at different levels of detail.

The "paradox" only arises if you insist that the report and the ledger must say the same thing. If you demand that the one-page summary should contain all the detail of the handwritten notebook. It cannot. That is not a failure. That is what summarizing means.

Spooky bookkeeping

And then there is the spookiest result in all of physics. Two particles are created together, then sent to opposite sides of a laboratory — or, in principle, opposite sides of the galaxy. Measure one, and you instantly know something about the other. Einstein called this "spooky action at a distance" and used it to argue that quantum mechanics must be incomplete.

But look at what "instantly know" actually means. It means: once you read Alice's report, you can update your prediction about Bob's results. That is not a signal traveling from Alice to Bob. It is a bookkeeping update — the same kind of thing that happens when you learn a company's revenue was higher than expected and you revise your estimate of its profit, without any new information about expenses.

The crucial test is this: can Bob tell, from his measurements alone, what Alice chose to measure? Can he detect any difference in his results based on what she did? The answer is no. His raw numbers look exactly the same regardless. No signal was sent. No influence traveled. The only thing that changed was the prediction you make after you compare notes — and comparing notes is bookkeeping, not physics.

The "spookiness" comes from confusing two things: an update to a prediction (which can happen as fast as information travels) and an influence on a physical system (which cannot travel faster than light). One is a revision of the report. The other would require a rewrite of the ledger. Quantum mechanics does the first. It does not do the second.

The part that gets personal

Every experience you have ever had arrived as a report.

Light hit your retina and your brain filed a summary: "red." Sound waves reached your ear and your brain filed another: "loud." You did not experience the light itself — the wavelengths, the photon counts, the electromagnetic oscillations. You experienced the record your nervous system produced. A compressed, stable, one-page version of something incomprehensibly detailed.

The record is stable — seeing red once and seeing red again feels the same, just as filing the same report twice gives the same report. The record throws away detail — you do not perceive individual photons, just as the annual summary does not list individual transactions. And the record depends on how you look — stare at the vase or stare at the two faces, depending on which report your brain files first.

Quantum mechanics is not stranger than the rest of physics. It is the first place where the difference between the ledger and the report becomes impossible to ignore. At the scale of everyday life, the two are close enough that you can pretend they are the same thing. At the atomic scale, you cannot. The act of filing the report — of forming a record, of compressing the mess into something stable — changes what is available to be found next. And the order in which you file changes what the reports say.

That is not a defect of quantum mechanics. That is what bookkeeping looks like when the books are small enough that your pen pushes the ink around.

Read the research

A Six-Birds' Eye View of Quantum Theory

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.