You are standing in a rainstorm. A billion water drops are falling around you — each with its own size, speed, and path. But that is not what you experience. You experience "rain." You feel "wet." You look up and see "gray."

These are summaries. Your nervous system took a billion separate events and compressed them into a handful of words your brain could use. And the compression worked — you reached for an umbrella, not a physics textbook.

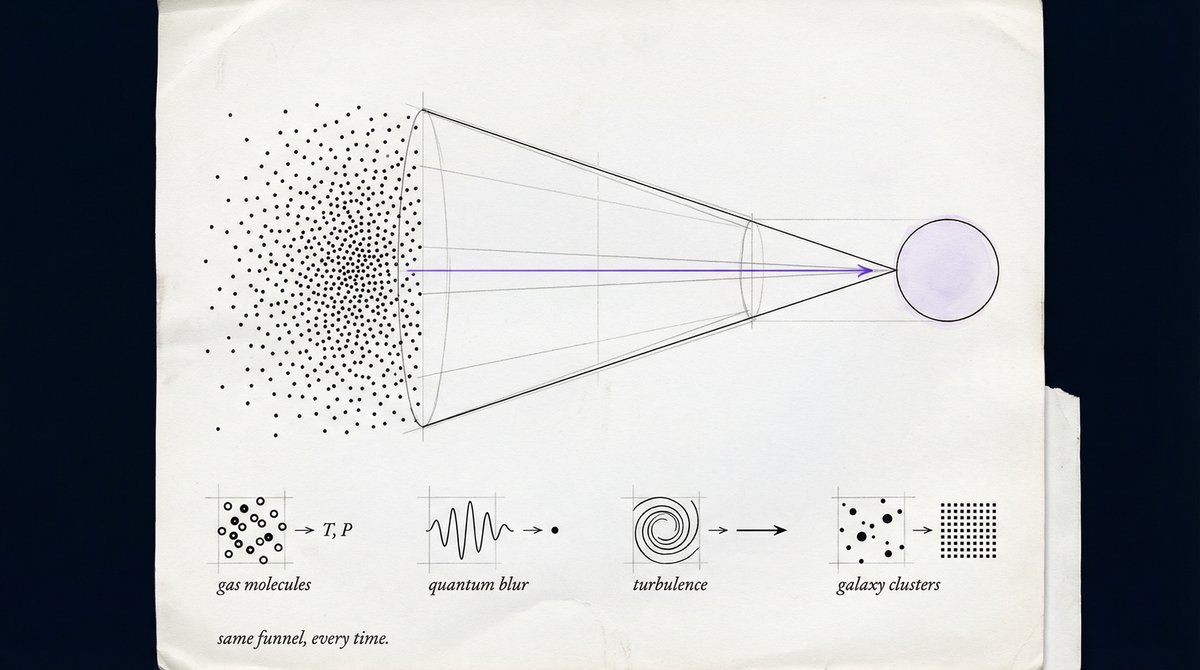

Physics does the same thing. Every theory of physics — from the equations that describe atoms to the ones that describe the expanding universe — is a compression. It takes an impossibly detailed picture of reality and squeezes it into something a human can calculate with. The details it throws away are different every time. But a surprising finding suggests that the structure of the squeezing is always the same.

The throwaway problem

When you say "it is raining," you have thrown away almost everything. Which drops are where. How fast each one is falling. The exact temperature of each drop. All gone. Replaced by a single word.

Usually this is fine. You do not need to track every drop to decide whether to bring an umbrella. The summary works.

But sometimes it does not. A pilot cares about drop size — large drops mean a different kind of danger than fine mist. A farmer cares about distribution — rain in one corner of the field does not help the other corner. The same "rain" compresses two very different situations into one word, and if you try to make a decision based on that word alone, you can get the wrong answer.

This is the dilemma at the heart of every theory of physics. You must compress — the full picture is too detailed to work with. But every compression throws something away. The question is: can you tell when what you threw away starts to matter?

Four compressions, one problem

Think of different physics theories as maps drawn at different zoom levels.

Zoom into a gas, and you see trillions of molecules bouncing off one another — each with a position, a speed, a direction. Zoom out, and all of that vanishes. In its place: temperature and pressure. Two numbers that tell you everything you need to run an engine.

Zoom into a quantum particle, and you see a blur of possibility — the particle is not here or there but somehow both. Zoom out, and the blur is gone. In its place: a solid object sitting in a definite spot.

Zoom into a rushing river, and you see whirlpools nested inside whirlpools — eddies at every scale, from meters to fractions of a millimeter. Zoom out, and the turbulence smooths into a current with a speed and a direction.

Zoom into the universe, and you see galaxies, clusters, voids, and filaments — lumps everywhere. Zoom out far enough, and you see a smooth, expanding space described by a single number: how fast everything is spreading apart.

Each of these is a compression. Each one keeps a few big-picture numbers and throws away a mountain of small-picture detail. The question is whether all four compressions are doing the same thing under the hood.

The order trick

Here is a question that turns out to be the same question in every branch of physics.

Imagine you are watching a scene through a frosted window. You can see shapes and colors but not fine detail. Something moves in the room — a person walks from one side to the other.

You can find out what happened two ways.

Path A. Watch the actual scene in high definition. See the person walk. Then look through the frosted glass at the result.

Path B. Start with the frosted view. Try to figure out what the person did using only blurry information. Evolve your blurry picture forward on its own.

If the frosting is mild — like squinting slightly — both paths give nearly the same answer. But if the frosting is heavy, they pull apart. Path A had high-resolution information during the action. Path B was guessing.

The gap between these two paths has a name in the emergence calculus: the route mismatch. And it turns out to be the single most revealing test you can run on any compression in physics.

Where the interesting physics hides

The route mismatch is not noise. It is not a rounding error or a sign that a theory is broken. It is structured information about exactly what the compression is costing you.

In the study of turbulence, the route mismatch tells engineers what the small whirlpools are doing to the big ones. Without that correction, computer simulations of airplane wings and weather systems quietly drift from reality. The mismatch is the price of ignoring the small stuff — and it is a price you can measure and pay, once you know it is there.

In cosmology, the route mismatch shows up when you try to average a lumpy universe into a smooth one. "Smooth it then evolve" gives a different answer than "evolve then smooth." That difference is a correction term. Some researchers think this correction — not a mysterious substance — might be part of what we have been calling dark energy.

In quantum mechanics, the route mismatch is the gap between "measure this first, then measure that" and "measure that first, then measure this." In the quantum world, the order of measurements genuinely changes the outcome. This is not a glitch. It is the compression telling you: what you chose to look at first changed what was there to find.

Three completely different branches of physics. The same structural gap. One diagnostic that works in all of them.

The same skeleton

Here is the punchline. Strip away the notation, the history, the tribal loyalties of different physics departments, and what you find underneath is the same architecture repeated over and over.

Every theory of physics does three things. First, it compresses — it chooses what to keep and what to throw away. Second, it checks whether the summary is stable: does compressing twice give the same result as compressing once? If your summary changes when you summarize the summary, something is off. Third, it measures the route mismatch: does the order of operations matter, and by how much?

A research program called Six Birds proposes that these three checks are universal. They work in quantum mechanics, in fluid dynamics, in the study of gases, and in cosmology. The same tests, the same structure, the same kinds of answers. The specific equations are wildly different. The skeleton is not.

That is what "every theory of physics is doing the same thing" means. Not that the theories agree. Not that they describe the same stuff. But that they all face the same structural problem — how to compress a richer picture into a simpler one without lying — and they all solve it using the same architecture.

The part that gets personal

This idea reaches beyond physics, if you let it.

Every model you carry in your head — of your job, your family, your country, yourself — is a compression. You took an impossibly detailed reality and squeezed it into something you could think with. You threw away most of the information. You kept what seemed to matter.

The question this framework teaches you to ask is not "is my model right?" Every model throws something away. The question is: what did I throw away? And does the order in which I think about things change my conclusions?

If the answer to the second question is yes — if thinking about money first and then relationships gives a different picture than thinking about relationships first and then money — then there is a route mismatch. Your model is hiding something. Not because it is bad, but because every compression hides something. The honest ones let you measure how much.

Next time someone tells you a situation is "just" politics, or "just" chemistry, or "just" bad luck — notice the compression. Ask what was thrown away to get that "just." Ask whether a different order would change the answer. You will be doing, in miniature, exactly what every theory of physics does. Because they are all doing the same thing.

Read the research

To Become a Stone with Six Birds: A Physics is A Theory

The full technical paper behind this article, with proofs, experiments, and reproducible code.

View paper landing pageThis article is part of the Six Birds Series — eight essays exploring one idea from different angles. Each accompanies a research paper in the emergence calculus program.